In 2020, Sohail Prasad and Samvit Ramadurgam left Forge, a leading private securities marketplace that they co-founded and led for many years, to create Destiny (D/XYZ) with the goal of launching a family of exchange-traded products that provide public market investors access to private market technology companies.

This piece is an exploration and analysis of Destiny both as a consumer product and as a fund issuer.

Why does Destiny matter?

Within the universe of problems that we can spend our time and effort trying to solve, those that address the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy for as many people as possible tend to excite me the most.1

Above, I include some representative startups (and former startups) that I believe address each layer of needs and thus have a meaningful and tangible impact on people and society:

Fusion energy and pre-fab homes to make our communities more sustainable and affordable

RNA therapeutics, virtual healthcare, and meditation apps to help people improve their physical and emotional wellbeing

Online learning platforms to democratize access to high-quality education

I would place Destiny squarely in the bucket of startups addressing safety needs - specifically, financial stability.2

We should financially benefit from our society’s innovations.

We happen to live in a remarkably entrepreneurial society that culturally and financially rewards those who create meaningful innovations in technology and business. This is not the result of chance, but rather the outcome of certain key developments over hundreds of years, from the invention of limited liability corporations to the cultivation of a strong community of early- and growth-stage investment funds ready to place large sums of capital behind visionary entrepreneurs.

Historically, founders would debut their companies on the public markets relatively early in their lifecycles, providing the public the opportunity to financially benefit from those companies’ continued growth.

For example:

Microsoft went public on March 13, 1986 at a ~$777M market cap. Today, Microsoft has a market cap of ~$1.9T, representing a gain of ~2,400x in the public markets (or ~900x adjusted for inflation).

Google went public on August 19, 2004 at a ~$23B market cap. Today, Google has a market cap of ~$1.2T, representing a gain of ~50x in the public markets (or ~30x adjusted for inflation).

The below chart illustrates that this is no longer true today. Tech companies are staying private for longer, meaning the financial benefits associated with their innovation and associated economic value creation largely accrue to the LPs and GPs of private investment funds rather than individuals.

Wealth matters insofar as it allows us to lead lives that align with our values and desires.

The direct result of this trend is a reduced ability for average individuals to compound their personal wealth. While one’s brokerage or retirement account typically does not impact day-to-day life, the power of financial compounding allows people to focus on other priorities: living more comfortably, dedicating their time to problems they care about rather than problems that pay well to solve, and spending more time on hobbies or with friends and family.

There are two potential solutions to this problem:

Option 1. We go back to a world pre-2000 where companies go public earlier in their lives.

This is unlikely. There are many driving forces for this dynamic of staying private longer, including the increasing abundance of private capital (rendering an IPO less necessary as a means to raise capital), the growing recognition that it may not always be in a company’s best interest to be beholden to Wall Street on a quarterly basis, the high costs of running a public company, and the growing viability of secondary rounds and private security marketplaces as means to provide liquidity for early employees and investors. It is difficult to gain conviction that this trend will reverse course anytime soon.

Option 2. We democratize access to private stock in leading technology companies.

“Democratize access to…” in the context of financial services is often a tricky balance to strike. For example, you want to avoid democratizing access to leverage, options, or exotic securities without ensuring that your users are informed on how to navigate these products and that your platform has proper controls in place. We need not look beyond this past year for a salient example: democratizing access to “yield” through crypto products like BlockFi and Celsius may not have been such a good idea after all.

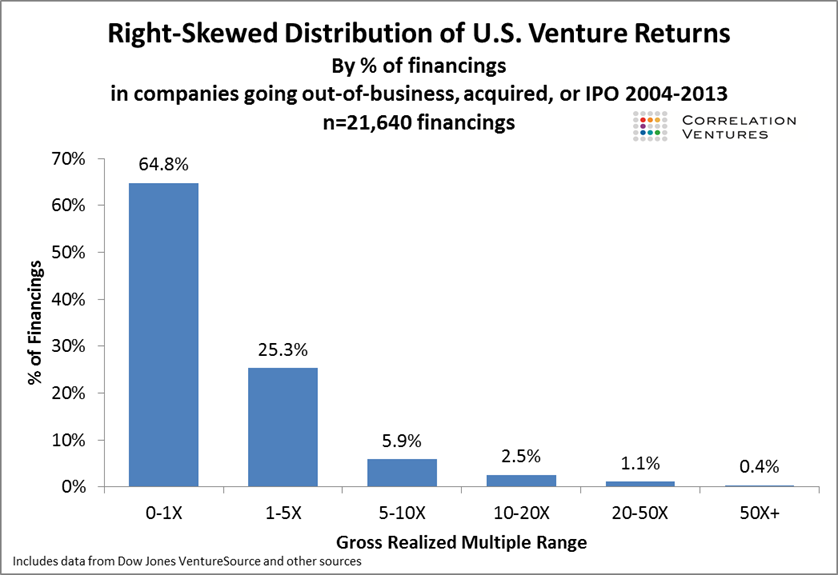

Categorically democratizing access to investing in private tech companies may not be a path worth exploring. Per the below chart, a staggering 65% of venture-backed companies failed to return 1x their invested capital, implying fund performance is heavily dependent on a few bets with outsized returns. Additionally, it is well understood that venture capital returns exist on a power law distribution, where the highest returns accrue to the few largest and most prominent firms.

However, democratizing access to investing in the subset of private tech companies that would likely have been public a decade or two ago (the likes of Stripe, SpaceX, and Klarna), but are not public today, seems like a worthy problem to address. If these scaled companies won’t go public, then retail investors may need to meet them where they are.

This is clearly the solution that entrepreneurs and investors have converged upon, as evidenced by the growth of crowdfunding platforms like SeedInvest and Republic, private securities marketplaces like Forge and CartaX, and now Destiny.

Crowdfunding platforms suffer from selection bias (the best private tech companies don’t need to go to crowdfunding platforms for capital), and while private securities marketplaces are a critical piece of infrastructure in this new financial ecosystem, they do not solve the problem discussed above. You cannot expect the average person to navigate the complexities of selecting and purchasing secondary stock, nor should we necessarily encourage this, given the lack of standardized reporting requirements for private companies.

Destiny promises to take on the burden of (1) conducting due diligence to select the most promising private tech companies and (2) navigating the complexities of acquiring equity or equity-like securities in private tech companies to ultimately offer retail investors a fund with exposure to the top venture-backed, US-based private tech companies.

Proper execution of this idea could make a meaningful dent in helping us return to a world in which we can all benefit from the generational companies being built around us.

A very brief history of Destiny

Destiny was founded in 2020 by Sohail Prasad and Samvit Ramadurgam.

Throughout 2021, Destiny raised $94M through a private offering of SAFEs from 220 investors to seed its first fund, Destiny Tech100.

Destiny Tech100 made its first investment on June 24, 2021: $3M into Superhuman Labs.

Christine Healey joined Destiny in November 2021 as Head of Private Markets and the third member (alongside Sohail and Samvit) of Destiny’s Investment Committee.

Since inception, Destiny Tech100 has invested $82M of capital in over 20 private companies, including SpaceX, Discord, Epic Games, and Stripe, and has $12.5M of remaining cash on its balance sheet. Due largely to unfortunate timing, this $82M has since been marked down to $54M, representing a -33% ROIC (as of September 30, 2022).

Destiny filed its first form N-2 with the SEC on May 13, 2022, signaling its desire to turn Destiny Tech100 into a publicly-listed closed-end fund under the ticker DXYZ through a public share offering.

A publicly-listed closed-end fund?

A quick aside on closed-end funds (CEFs), as understanding closed-end funds is key to understanding Destiny. There are several types of closed-end funds: interval funds, business development companies, and publicly-traded closed-end funds. To avoid confusion, I will be referring to publicly-traded closed-end funds.

Closed-end funds sell their shares in a public offering (IPO).

For example, DXYZ might offer 10M shares at $10 each in its public offering, raising $100M for its fund from public investors. This would add to the $94M DXYZ has raised through its private offering of SAFEs, and barring any follow-on offerings (certainly possible) or raising debt (which seems unlikely), this would represent all of the capital DXYZ has to invest.

These publicly-traded closed-end funds trade on public markets (as you might expect) and only trade on a secondary basis (you aren’t trading with the issuer, but rather another investor).

Closed-end funds do not issue or redeem shares on a continuous basis like ETFs.

ETF sponsors are required to support redemptions of ETF shares (i.e., a large investor can gather a certain number of ETF shares and redeem them for the equivalent underlying basket of securities). Closed-end funds do not need to redeem shares, which allows them to invest in less liquid assets, like equity in private companies.

Closed-end funds frequently trade at a discount or premium to NAV (net asset value). Due to the inability to redeem shares for the underlying assets or securities, CEF market prices are largely determined by supply and demand and can become decoupled from the fair value of the underlying assets.

I include a fun chart below with the historical premium / discount to NAV for GBTC (Grayscale’s Bitcoin CEF), which has ranged from >100% premium to NAV to now closer to a 50% discount to NAV.

Some observations on DXYZ

I read through Destiny’s latest Form N-2, which details the fund’s strategy, operations, and financials.

In addition to following leading venture investors, Destiny conducts its own due diligence.

Destiny notes that they will take into account factors like TAM, market / company growth rate, recent financing rounds, business model, network effects, culture / ESG, “as well as other indicators that may be strongly correlated with higher or lower valuations” in their investment process.

It’s a delicate balance to reach. Too much focus on due diligence and active portfolio management, and public investors must gain conviction in Sohail’s, Samvit’s, and Christine’s ability to be consistently effective capital allocators. Institute a minimal filter on investments, and public investors must accept the risk that certain bad investments that may have otherwise been weeded out through proper due diligence will find their way into the mix.

This is not to say that they aren’t / won’t become great investors. Sohail and Samvit have meaningful experience investing at the seed level, which may or may not translate to mid- and later-stage growth, but investing in Sohail, Samvit, and Christine’s VC fund, which happens to be publicly-traded, feels different than investing in an index of high-growth, venture-backed companies.3

Side note: This also raises the question - to what extent will Destiny even be able to conduct meaningful due diligence? They have primarily made secondary investments to date, and the amount of information available in secondary transactions is likely less than the amount available in a primary raise (and even within a primary raise, the lead investor might receive more information by way of increased management exposure).

Destiny won’t just invest in common equity.

Destiny will seek to gain equity-like exposure to private tech companies through equity, equity-linked securities (e.g., warrants, preferred stock, convertible debt with a significant equity component, forward contracts, swaps, etc.), and units / shares of venture funds and private equity funds. This is unsurprising, as these equity-linked securities are common (increasingly so recently) within this world.

Notably, they leave the door open to investing in other private funds (although, they limit this to 15% of net assets). It’s hard to imagine the rationale behind allocating DXYZ money to other funds - there would need to be certain assets that they so desperately want exposure to that they would be willing to expose their shareholders to something like an incremental 2% management fee / 20% carry (in addition to DXYZ’s fees) on that capital. They have currently allocated 100% of their investments to private tech issuers (companies) rather than private funds, and I would expect that to remain the case.

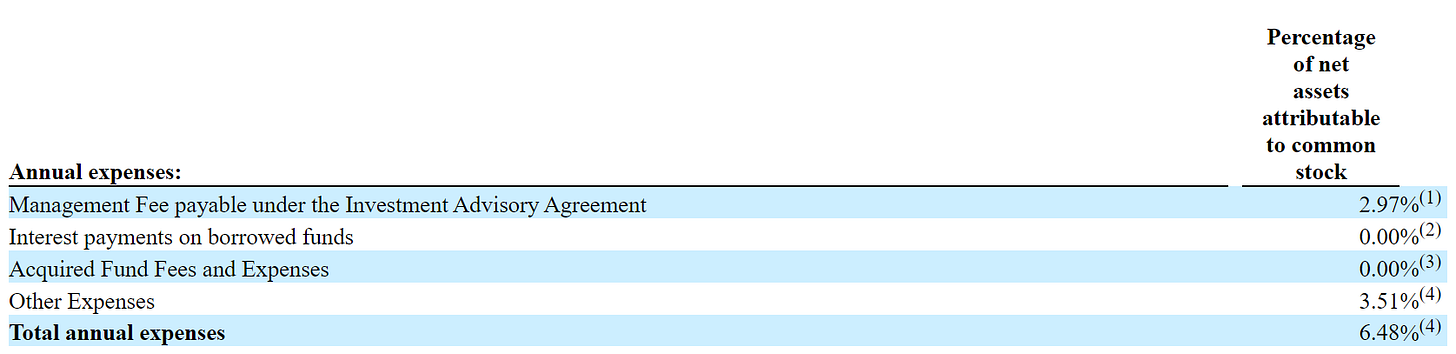

This product isn’t cheap!

DXYZ plans on charging 2.5% management fees on gross assets (increasing from 2.0% on invested capital when they list on the NYSE).

This fee is charged on gross assets, rather than net assets, meaning if DXYZ decides to use leverage, they will also charge management fees on that borrowed capital. This likely won’t become relevant, as I wouldn’t expect them to lever up on an asset class perceived4 as very risky. If you are curious, you can read more about the relationship between leverage and expense ratios in closed-end funds here.

This seems expensive?

Grayscale’s GBTC CEF, which only holds BTC, charges 2.0% in management fees. However, DXYZ is actively managed, whereas GBTC is not, so one could argue DXYZ can charge more.

ARK’s Innovation ETF (ARKK), which is actively managed and invests in public tech companies, charges 0.75% in management fees, which is considerably lower. However, ETFs tend to be significantly cheaper.

It’s actually even more expensive.

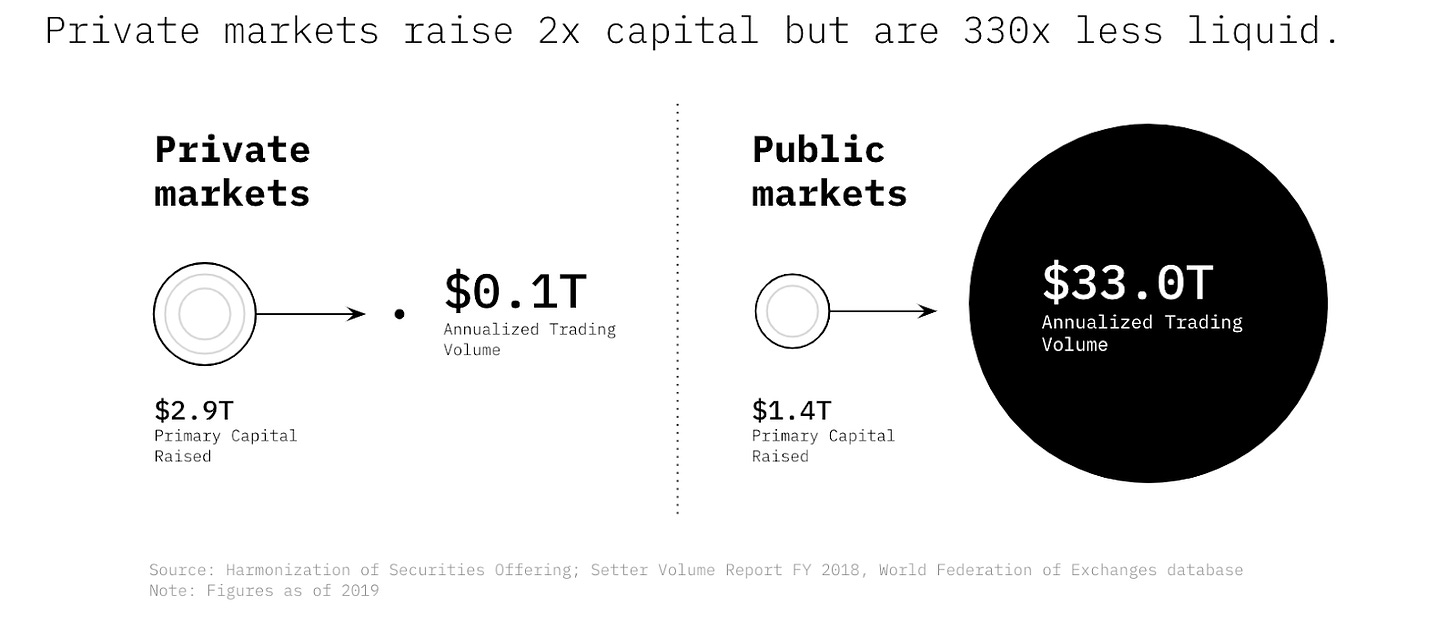

It’s important to consider the full expense ratio, not just management fees. Destiny estimates total annual expenses as a percentage of net assets of ~6.5%.

Destiny also provides this helpful breakdown of the fees an investor should expect to pay on an illustrative $1,000 investment.

You can back into a ~6.4% expense ratio given their estimates (close enough to the ~6.5% shown above). Obviously, the math doesn’t work when you assume an annual return of 5.0% and an annual expense ratio of 6.4%.

Okay. It actually shouldn’t be that expensive after they launch.

Their estimated expense ratio is based on their current fiscal year (ending December 31, 2022), so we will need to adjust a few figures to get to a more realistic run-rate figure.

We can reduce management fees from 2.97% to 2.5%. Today, they are charging 2.0% on invested capital. Due to poor investment performance (hard to blame them given the environment), net assets are meaningfully lower than invested capital, so this 2.0% on invested capital shows up as 2.97% on net assets. Regardless, this will change to 2.5% post-launch, as the 2.5% is applied to gross assets, which should equal net assets (assuming they don’t use leverage).

We can reduce other expenses from 3.51% to 1.0%. The 3.51% includes accounting, legal, auditing, organizational / offering, and other administrative costs. This presumably captures a lot of the up-front costs to launching DXYZ over the past year, and those costs wouldn’t persist in a steady state. Fundrise’s Innovation Fund, which is slightly more developed than DXYZ, reports other expenses at 1.12%5 of net assets, so perhaps 1.0% is reasonable.

We can keep interest payments and acquired fund fees at 0%. As discussed above, leverage is unlikely, so there shouldn’t be any interest expense. Acquired fund fees are the “indirect costs of investing in other investment companies”. Destiny expects this to remain less than 1 basis point, so we can assume the same.

We can also adjust annual estimated returns to better reflect reality. Median venture capital returns seem to be around 10%. The variance is massive, but let’s assume 10% for this analysis.

A revised analysis with an annual return of 10.0% and an expense ratio of 3.5% still only produces a 10-year investment CAGR of 7.2%. This remains below the average annual S&P 500 index return of ~10%, which investors can get access to through minimal- or no-fee ETFs.

But, if you assume an annual return of ~13.5% (or higher), this starts to get interesting.

Let’s talk about risk.

You may have noticed that while the median return across global venture capital firms is a relatively healthy ~10%, many of the bottom-quartile managers deliver negative returns. Is this an asset class that we really want to expose to retail investors?

I would first note that DXYZ focuses on companies valued over $750M and with minimal debt. This should lead to a significantly lower risk profile than venture capital broadly, so there should be lower variance in returns.

I would also note that sufficient diversification, even across earlier-stage investments, leads to higher median returns with lower variance. Institutional Investor ran a Monte Carlo simulation comparing a fund with 15 investments to a fund with 500 investments, with the results shown below.

The second bar in the chart below shows the impact on returns when the VC portfolio expands to the recommended portfolio size of 500 investments. The outcome: The dispersion for the VC portfolio returns tightens to a range of 10 to 17 percent. This range of returns from bottom to top quartile is similar in size to that of public equity funds. With suitably high diversification, VC indeed becomes an investment-grade asset.

The Monte Carlo simulation also shows that funds with 500 portfolio firms have a 13.5 percent median return, compared to 10 percent for the 15-investment funds. In fact, the returns of the worst (fifth percentile) ultra-large VC funds are the same as the median returns from undiversified VC funds.

I would recommend checking out this article if you have questions like, “why doesn’t every venture fund do this, then?”, but that is out of scope of this piece. The key question here is whether DXYZ will reach a sufficient level of diversification.

Institutional Investor notes that 100 companies is the absolute minimum when it comes to diversifying in the venture asset class. Again, given DXYZ’s focus on larger companies, you arguably don’t need quite as many investments.

So far, DXYZ has only invested in a little over 20 companies. One reason why venture firms tend to make more concentrated bets is purely logistical - it can become a lot of work to manage hundreds of investments. DXYZ will need to prove its ability to not only get access to but also manage the administrative headache of investments across 100 high-quality private tech companies.

Let’s assume that a portfolio of 100 mid- and growth-stage companies behaves similarly to a portfolio of 500 venture-backed private companies across all stages. If DXYZ is able to generate annual returns of 13.5% (the median return for a portfolio of 500 venture-backed private companies), we start to reach a long-term investment CAGR (post-fees) that exceeds that of the S&P 500 (see above chart).

What’s next for Destiny?

Let’s get some of the reasons Destiny might not succeed out of the way first, since this is a lot less fun.

Destiny might be too early.

There are countless examples of otherwise promising startups failing simply because they are too early. Capital can be limited and can run out before critical “pre-requisites” for success are established.

One possible pre-requisite for Destiny’s success is sufficient liquidity within private markets. Over 80% of DXYZ’s current holdings have been acquired through secondary purchases. Forge, one of the largest secondary share marketplaces, reported a 3.3% net take rate on transactions in 2021 (up from 2.6% in 2020).6 Every secondary transaction DXYZ makes to acquire or offload shares will lead to meaningful value leakage via marketplace fees. Naturally, these fees will come down as the industry matures, but that may take some time.

Destiny might not be able to differentiate itself versus other products in the market.

Destiny isn’t the first company to offer retail investors access to venture investments and won’t be the last. A number of similar retail-focused investment vehicles have been formed over the past couple years, each with a slightly different approach to structure and portfolio composition. I include a few of them below.

There are two vectors of differentiation needed for success:

Destiny will need to offer a differentiated product for retail investors. So far, they are clearly different in (1) their objective of indexing the private tech company landscape and (2) their (soon-to-be) publicly-listed structure, which should theoretically have superior liquidity. There are a couple caveats to this:

(1) This is a more difficult objective to execute against (it’s not easy to get access to all of these private companies).

(2) Liquidity is entirely conditional on the amount of secondary investor demand.

Destiny will need to offer a differentiated product for companies. Secondary trading is expensive (at least for now), so Destiny should be looking to make primary investments when possible. As capital has become increasingly cheap (although, this is changing), companies have increasingly selected investors for their value-add (a nebulous term, I know, but indicative of how founders are thinking). To get allocation in primary rounds, Destiny will need to make a compelling case to companies that they deserve a spot on their cap tables over other traditional venture firms and these more direct competitors.

For example, from some of their competitors:

Companies that the ARK Venture Fund invests in can tap into ARK’s years of proprietary research expertise as well as their network of co-investors, public and private companies, founders, and academics. They also benefit from ARK’s brand awareness among retail investors and social media presence.

The Fundrise executive team has spent decades actually building technology companies. Moreover, with over 100 software engineers and product managers on staff, we believe we have more real software depth and expertise than many venture funds. […] We believe that this real world experience and broader mandate/mission to democratize the financial markets will not only be an actual differentiator in what has become a commoditized space but will also make us attractive to other fellow tech company founders and leaders with whom we have a shared history.

But, let’s be optimistic!

This is a massive opportunity, so what does that mean for Destiny as an issuer?

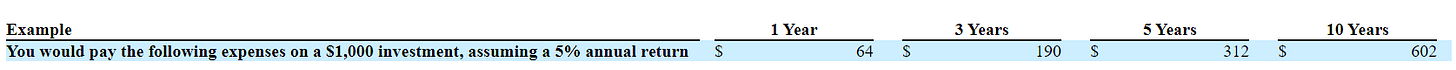

Private markets are flush with capital. Tribe Capital estimates $2.9T of primary capital raised as of 2019. Carta, a leading equity management platform, reports $2.5T of assets on their platform, which likely represents a sizeable percentage of all primary capital out there.

Let's assume DXYZ launches at the beginning of 2024 with a $1.0B IPO (well below 0.1% of all private capital). This may not be entirely unreasonable, given ARK Invest took ~8 years to grow to ~$13.5B AUM7, implying an average AUM growth of ~$1.6B per year.

A successful launch of DXYZ could value Destiny (the issuer, not the fund) anywhere from $70M to $100M, based on a range of 18.0-26.0x CY24E NOPAT8, with incremental upside based on the expectation of future fund launches. Not bad for a four-year old startup!

Destiny won’t stop at DXYZ. The perpetual nature of CEFs and their permanent capital base imply a considerably de-risked revenue stream, so Destiny will want to continue launching new funds (like Bio100, Fintech100, or Space100, as Mario hypothesizes in his briefing), as long as there is investor appetite. It doesn’t take a large mental leap to imagine the value creation that could result from proper execution and sufficient investor demand over the next 5 to 10 years.

If you made it this far, thanks for reading! I largely wrote this piece to organize my thoughts around a company that I think is trying to solve a problem that matters. If it happens to be helpful and/or interesting to anyone else, even better.

If you have any thoughts, or if I got something wrong, or if this stuff just excites you, reach out! I love meeting like-minded people and welcome any and all feedback.

Appendix

I didn't know where else to fit this, but found it quite interesting. The concept of providing public exposure to private companies is not a novel one. In 2010, SuRo Capital Corp (f.k.a. Sutter Rock Capital Corp.) was founded as a publicly-listed closed-end management investment company with the goal of investing in high-growth, venture-backed private companies. SuRo currently holds positions in private companies like Whoop, Varo Money, Course Hero, and Locus Robotics. However, they have not executed well on this vision with a 5-year trailing share price performance of -58% (compared to 91% for VGT, Vanguard's Information Technology ETF, and 52% for the NASDAQ index). This is likely obfuscated by some of SuRo's other operations and intricacies (e.g., SPACs, use of leverage, etc.), nor does SuRo promise to index the private tech company landscape, but regardless, they have not solved this problem for retail investors. Thank you to a reader (who works at SuRo!) for reaching out and pointing out that you need to look at dividend-adjusted performance, as dividends are primarily how SuRo delivers returns to investors. Including dividends, SuRo has a 5-year trailing total return of 64% (compared to 112% for VGT, Vanguard’s Information Technology ETF, and 61% for the NASDAQ index).

I do not speak on behalf of organizations I work(ed) for or invest(ed) in. This content is for information purposes only and is not intended to be investment advice.

Thanks to Dev Patale, Jonathan Fung, and Will Jack for their feedback and thoughts.

With the possible exception of the role that many tech companies, especially in social media, seek to play as a source of esteem

While I acknowledge it may be a stretch to place Destiny as it exists today in this bucket, I can see a future in which the financial infrastructure supporting Destiny matures, allowing Destiny to offer (relatively) low-cost indices of the private tech company landscape that become staple investments.

Note that while Destiny never uses the word “index” on their website or in their SEC filings, they directly compare DXYZ to the S&P 500 and NASDAQ 100 on their landing page, strongly implying their desire for DXYZ to be seen as an index, rather than a typical actively-managed private fund.

I use the word “perceived” because as I note later in this piece, the venture asset class is not nearly as risky as many believe (with sufficient diversification).

Total reported net assets across all ARK funds (ARKK, ARKW, ARKG, ARKQ, ARKF, ARKX, PRNT, and IZRL) as of January 31, 2023

As CEFs do not run the risk of fund outflows due to share redemptions, one could argue that a CEF issuer deserves a higher multiple than an ETF issuer like WisdomTree or iShares.